Implantable cardiac pump offers hope to children awaiting heart transplant

最近審查:14.06.2024

A small implantable cardiac pump that could help children wait for a heart transplant at home rather than in hospital has shown good results in a first-stage clinical trial.

The pump, a new type of ventricular assist therapy, or VAT, device is surgically attached to the heart to enhance its circulatory function in those with heart failure, allowing time to find a donor hearts. The new pump may close an important gap in pediatric heart transplant care.

In a study evaluating seven children who received a new pump to support their weakened hearts, six ended up having heart transplant, and one child had a heart recovery, making transplantation unnecessary. The results were published in The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. The study was led by Stanford School of Medicine and included multiple medical centers in the United States.

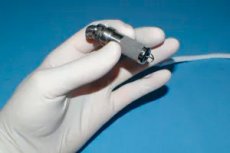

If the initial results are confirmed in a larger study of the device, the wait for a heart transplant could become easier for young children and their families. The new pump, called the Jarvik 2015 ventricular assist device, is slightly larger than an AA battery and can be implanted in children weighing as little as 8 kilograms. With an implanted pump, children can do many normal activities while they wait for a heart transplant.

In contrast, the only available ventricular assist device to support young children with heart failure, a pump called the Berlin Heart, is not implanted; it is the size of a large suitcase. It weighs from 27 to 90 kilograms, depending on the model, and is attached to the child using two cannulas, almost as large as garden hoses.

Berlin Heart also has a fairly high risk of stroke and requires hospitalization in most cases, meaning children often spend months in hospital waiting for a donor heart. As a result, the burden for children awaiting heart transplantation is much higher than for adults who have implanted heart pumps, who are typically discharged from the hospital with similar diagnoses.

"While we are extremely grateful for the Berlin Heart, a life-saving device, ventricular assist devices for adults have improved every decade, and in pediatrics we use technology from the 1960s," said Dr. Christopher Almond, lead author of the study and a pediatric cardiologist and professor. Pediatrics at Stanford School of Medicine.

Implantable ventricular assist devices have been available for adults for more than 40 years, Almond notes. Not only do these devices fit inside patients' chests, but they are also safer and more comfortable to use than external devices such as the Berlin Heart. Patients can live at home, go to work or school, walk and ride a bike.

The gap in pediatric technology is a problem for other devices designed to help children with heart disease, and in pediatrics in general, Almond said. “There is a huge difference in the medical technologies available to children and adults, which is an important public health issue that markets are struggling to address as conditions such as heart failure are rare in children," he says.

Senior author of the study is Dr. William Mahle, chairman of the department of cardiology at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta.

Far fewer children than adults need heart transplants, leaving little incentive for medical companies to develop a miniaturized pump for children. But the lack of a small ventricular assist device for children puts a strain on the medical system, as children assigned to Berlin Heart rack up large medical bills and can take up hospital beds in specialized cardiovascular care units for months, potentially reducing the availability of those beds for other patients.

Promising initial results

The Jarvik 2015 ventricular assist device trial included seven children with systolic heart failure. The condition affects the heart's largest pumping chamber, the left ventricle, which pumps blood from the heart throughout the body. In six of the children, systolic heart failure was caused by a condition calleddilated cardiomyopathy, in which the heart muscle grows and weakens and does not pump blood properly. One child's heart was weakened by complete heart block (electrical heart failure) due to lupus, an autoimmune disease. All children in the trial were on the heart transplant waiting list.

Each child had a Jarvik 2015 device surgically implanted in the left ventricle, the largest pumping chamber of the heart. At the same time, everyone was given medications to prevent blood clots and reduce the risk of stroke. At the time the pumps were installed, the children were between 8 months and 7 years old and weighed between 8 and 20 kilograms. The pump can be used for children weighing up to 30 kilograms.

If the new pump is approved by medical regulators, doctors estimate that about 200-400 children worldwide each year could be candidates for its use.

The trial assessed whether the pump could support patients for at least 30 days without stopping or causing a severe stroke. The researchers also collected preliminary safety and effectiveness data to help them design a larger, pivotal trial for possible Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

Although the pump was originally designed to allow children to wait for a heart transplant at home, since they were participating in a clinical trial, participants remained in the hospital under observation until they received a heart transplant or recovered. The researchers tracked participants' blood pressure, an indicator of the risk of blood clots and stroke; measured hemoglobin levels to see if the pumps were destroying red blood cells; and monitored patients for other complications.

The average time children used the pump was 149 days. Six children underwent heart transplantation, one child recovered.

Several children have had complications with the new pump. The child whose heart recovered had an ischemic stroke (due to a blood clot) when the heart became strong enough to compete with the pump. The pump was removed and the child continued to recover and was alive a year later. Another patient had right side heart failure and was transferred to the Berlin Heart pump while awaiting transplant.

For most patients, complications were manageable and generally consistent with what doctors expect when a child is connected to a Berlin Heart pump.

Quality of life questionnaires showed that most children were not bothered by the device, did not feel pain from it, and were able to participate in most play activities. One family reported that their baby with the pump was able to maintain much more mobility than his older brother, who was previously supported by the Berlin Heart pump.

Larger trial planned The National Institutes of Health has awarded funding for an expanded trial that will allow researchers to further test the utility of the new pump and collect data to submit to the FDA for approval. The next phase of the study begins now; researchers plan to enroll the first patient by the end of 2024. The research team plans to enroll 22 participants at 14 medical centers in the United States and two sites in Europe.

"We are excited to begin the next phase of the study," Almond said. "We've overcome a number of challenges to get the work to this point, and it's exciting that there may be better options in the future for children with end-stage heart failure who need a pump that acts as a bridge to transplantation."