Researchers from the Netherlands Institute of Neuroscience have begun to study a complex question: what happens in the human brain that may be “stuck” between sleep and wakefulness?

Most of us imagine a somnambulist as a person who unconsciously walks with his eyes closed and his arms extended forward. In fact, sleepwalkers typically walk with their eyes open and are able to interact with their surroundings. Sleep scientists call this abnormal sleep behavior "parasomnia", which can include simple actions such as sitting up in bed looking embarrassed, but also more complex, such as getting out of bed, moving around, or screaming with a scared expression.

Although this type of parasomnia is more common in children, approximately 2-3% of adults experience it regularly. Parasomnias can be distressing for both the sleeper and his bed partner. "Survivors may harm themselves or others during episodes and later feel deeply ashamed of their actions," explains Francesca Siclari, director of the Dream Lab.

Studying parasomnias in the laboratory Siclari and her team conducted this study to better understand what happens in the brain during parasomnias. "Dreams used to be thought to occur in only one stage of sleep: REM sleep. We now know that dreams can occur in other stages as well. Those who experience parasomnias during non-REM sleep sometimes report dreamlike experiences and sometimes seem completely unconscious (i.e., on autopilot)."

To understand what drives these differences in experience, Siclari and her team examined the experiences and brain activity patterns of parasomnia patients during non-REM sleep.

Measuring brain activity during a parasomnia episode is not an easy task. The patient needs to fall asleep, experience the episode, and record brain activity during movement.

"There are very few studies that have overcome this. But thanks to the multiple electrodes we use in the laboratory and some specific analysis methods, we can now get a very clean signal even when patients move," explains Siclari.

Siklari's team can induce a parasomnia episode in the laboratory, but this requires two consecutive recordings. During the first recording, the patient sleeps normally. This is followed by a night when the patient is allowed to sleep only in the morning after a sleepless night.

During this recording, when the patient enters the deep sleep phase, he is exposed to a loud sound. In some cases, this leads to an episode of parasomnia. After the episode, the patient is asked what was on his mind.

In 56% of episodes, patients reported dreaming. "Often it was associated with impending misfortune or danger. Some thought the ceiling would collapse. One patient thought he had lost his child, looked for him in bed, stood up in bed to save ladybugs sliding along the wall and falling," explains Siclari.

"In 19% of cases, patients experienced nothing and simply woke up to find themselves doing something as if in a trance." Another small proportion reported that they experienced something, but could not remember what it was.

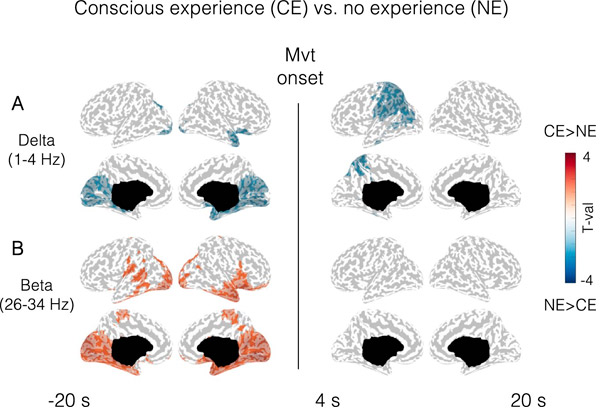

Based on these three categories, Siclari's team compared the measured brain activity and found clear parallels. "Compared with patients who did not experience anything, patients who dreamed during an episode had brain activity similar to brain activity during dreams, both before and during the episode," Siclari adds.

"Whether the patient is completely unconscious or dreaming seems to depend on the patient's state at the time. If we activate the brain when they are probably already dreaming, they seem to be able to 'do something-' then' from this activation, whereas when their brain is largely 'deactivated', simple actions occur without experience.

"Interestingly, patients almost never mention the sound that triggered the parasomnia episode, but instead talk about some other impending danger. The louder we make the sound, the higher the chance of triggering the episode."

Next Steps Since this is only the first step, there is much scope for further research. "The ideal would be to create a system to record sleep at home in more people, where they may also have more complex and frequent episodes. We would also like to replicate this kind of research in people experiencing parasomnias during REM sleep. By measuring brain activity "As in this study, we hope to eventually better understand which neural systems are involved in different types of parasomnias," says Siclari.

Although there is still much research to be done, Siclari is confident that her work can provide valuable knowledge. "These experiences are very real for patients, and many have already felt relief by sharing them with us. As with previous studies, our study provides insight into what they experience, which is educationally valuable.

"In addition, our work may help develop more specific drug interventions in the future. Parasomnias are often treated with non-specific sleep medications, which are not always effective and may have side effects. If we can determine which neural system is working abnormally, we will ultimately Eventually we will be able to try to develop more specific treatments."

The study was published in Nature Communications.