4 月 23 日,在科罗拉多大学医学院的年度研究日上,医学博士、理学硕士 Christine Swanson 介绍了她由美国国立卫生研究院资助的临床研究,该研究旨在研究充足的睡眠是否有助于预防骨质疏松症。

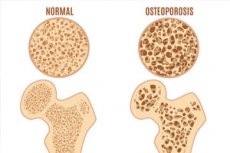

“骨质疏松症的发生原因有很多,例如激素变化、衰老和生活方式,”内分泌、代谢和糖尿病科副教授斯旺森说道。“但我遇到的一些病人,他们的骨质疏松症无法解释。”

因此,寻找新的风险因素并关注生命过程中发生变化的事物(例如骨骼)非常重要——睡眠就是其中之一,”她补充道。

骨密度和睡眠如何随时间变化

斯旺森说,人们在20多岁时达到所谓的骨密度峰值,男性的骨密度高于女性。这个峰值是决定老年骨折风险的主要因素之一。

达到峰值后,人体的骨密度会在几十年内保持大致稳定。然后,随着女性进入更年期,她们会经历加速的骨质流失。随着年龄的增长,男性的骨密度也会下降。

睡眠模式也会随着时间而改变。随着年龄的增长,人们的总睡眠时间会减少,睡眠的构成也会发生变化。例如,睡眠潜伏期(即入睡所需的时间)会随着年龄的增长而增加。另一方面,慢波睡眠(即深度恢复性睡眠)会随着年龄的增长而减少。

“改变的不仅仅是睡眠的持续时间和内容。男性和女性的昼夜节律阶段偏好也会随着生命周期而改变,”斯旺森说道,他指的是人们对何时睡觉和何时起床的偏好。

睡眠与我们的骨骼健康有何关系?

斯旺森说,控制我们内部时钟的基因存在于我们所有的骨细胞中。

当这些细胞重新吸收并形成骨骼时,它们会向血液中释放某些物质,使我们能够估计出在任何特定时刻发生的骨转换量。”

Christine Swanson,医学博士,理学硕士,科罗拉多大学医学院讲师

这些骨吸收和骨形成的标志物遵循昼夜节律。她表示,骨吸收标志物(即骨骼分解的过程)的节律幅度比骨形成标志物的节律幅度更大。

她说:“这种节律可能对正常的骨骼代谢很重要,并表明睡眠和昼夜节律的紊乱可能会直接影响骨骼健康。”

研究探讨睡眠与骨骼健康之间的联系

为了进一步探索这种联系,斯旺森及其同事研究了骨转换标志物如何应对累积睡眠限制和昼夜节律紊乱。

在这项研究中,参与者被置于一个完全受控的固定环境中。参与者不知道时间,并且每天的作息时间是28小时,而不是24小时。

“这种昼夜节律紊乱是为了模拟夜班工作时所经历的压力,大致相当于连续三周每天向西飞行跨越四个时区,”她说。“该方案还导致参与者的睡眠时间减少。”

研究小组在干预开始和结束时测量了骨转换标志物,发现睡眠和昼夜节律紊乱会导致男性和女性的骨转换发生显著的不利变化。不利变化包括骨形成标志物的下降,且与老年人相比,年轻人(无论男女)的下降幅度显著更大。

此外,还发现年轻女性的骨吸收标志物显著增加。

斯旺森说,如果一个人形成的骨骼减少,而随着时间的推移,吸收的骨骼数量相同或更多,则会导致骨质流失、骨质疏松症和骨折风险增加。

她说:“性别和年龄可能发挥重要作用,年轻女性最容易受到睡眠不足对骨骼健康的不利影响。”

她补充说,该领域的研究仍在继续。