A fully functioning immune system is essential to maintaining a healthy body, and macrophages play a critical role in maintaining strong immune responses against infections.

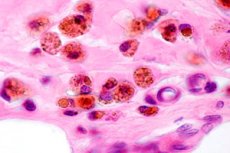

A macrophage is a type of white blood cell that destroys microorganisms, removes dead cells, and stimulates the action of other immune cells. These cells play a key role in initiating, maintaining and resolving inflammation, but their functionality declines with age, leading to a deterioration of the immune system. This results in increased susceptibility to infections and autoimmune diseases in the elderly population.

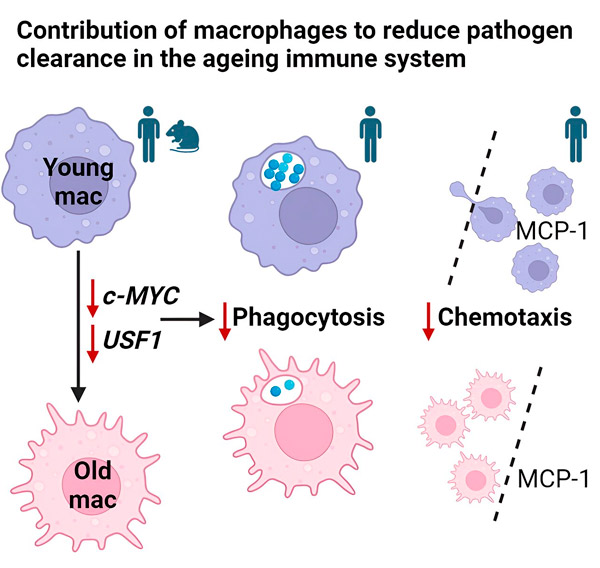

The study, published in Cell Reports, is the first to reveal that defects in macrophage function are driven by the MYC and USF1 transcriptional programs.

Research led by Charlotte Moss, Dr Heather Wilson and Professor Endre Kiss-Toth has identified a possible culprit for this decline: two critical molecules inside macrophages, MYC and USF1, which begin to malfunction with age.

Macrophages, often called the body's "garbage trucks", are responsible for ingesting and eliminating foreign particles, including debris and pathogens. The study showed a significant decrease in the efficiency of macrophages isolated from older people compared to young people. These aging macrophages showed decreased phagocytosis (the process of ingesting foreign particles) and decreased chemotaxis (the ability to migrate toward threats).

Confirming this connection, the researchers artificially reduced the activity of MYC and USF1 in young macrophages. This manipulation resulted in a functional decline that resembled the characteristics of older human macrophages. This finding strongly suggests that MYC and USF1 play an important role in maintaining optimal macrophage function.

The research goes beyond simply identifying the culprits. It examines how decreased MYC and USF1 activity may affect macrophages. The researchers speculate that these changes may disrupt the functioning of genes responsible for the cell's internal cytoskeleton, a network of threads that provides structure and movement.

This disorder may interfere with the macrophage's ability to move and ingest foreign particles. Additionally, altered MYC and USF1 activity may affect how macrophages interact with their environment, further impairing their ability to fight infection.

This study represents a significant breakthrough in understanding the mechanisms of age-related immune decline.

Graphic drawing. Source: Cell Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114073

By identifying MYC and USF1 as potential culprits, the study paves the way for the development of new therapeutic strategies. By specifically targeting these molecules or their gene products, researchers can improve macrophage function in older adults, which could lead to a stronger immune response and improved resistance to infection.

It is important to note that the study included healthy volunteers and did not include people with pre-existing age-related diseases. In addition, the studies were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings in a larger population and to explore whether these findings can be translated into effective therapies.

The identification of MYC and USF1 as potential targets for intervention represents a significant advance. This study opens the way for future strategies to strengthen the immune system in older adults, ultimately promoting healthier aging.

"Understanding why the immune system stops effectively fighting infections in old age is key to developing treatments that can reverse this process. Our work reveals the molecular details of aging in human phagocytes for the first time, and we believe this new understanding is now allows us to test the effectiveness of various interventions, including diet, lifestyle and even potential drugs aimed at reversing the aging of the immune system," says Endre Kiss-Toth.