Study finds chronic wasting disease unlikely to jump from animals to humans

最近審查:14.06.2024

A new study of prion diseases using a human brain organoid model suggests that there is a significant species barrier preventing the transmission of chronic wasting disease (CWD) from deer, elk and fallow deer to humans. The results, obtained by National Institutes of Health (NIH) scientists and published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, are consistent with decades of similar research in animal models conducted at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases ( NIAID) NIH.

Prion diseases are degenerative diseases found in some mammals. These diseases are mainly associated with deterioration of the brain, but can also affect the eyes and other organs. Disease and death occur when abnormal proteins fold incorrectly, clump together, attract other prion proteins to the same process, and ultimately destroy the central nervous system. There are currently no preventative or therapeutic treatments for prion diseases.

CWD is a type of prion disease found in deer, which are popular game animals. Although CWD has never been identified in humans, the question of its potential transmission has remained relevant for decades: Can people who eat meat from CWD-infected deer get sick with prion disease? This question is important because another prion disease, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or mad cow disease, emerged in the UK in the mid-1980s and mid-1990s. Cases have also been found in cattle in other countries, including the United States.

Over the next decade, 178 people in the UK who were thought to have eaten meat contaminated with BSE became ill with a new form of human prion disease, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and died. Researchers later determined that the disease had spread among cattle through feed contaminated with an infectious prion protein.

The disease's route from feed to cattle to people has scared people in the UK and put the world on alert for other prion diseases spread from animals to people, including CWD. CWD is the most transmissible of the prion disease family, demonstrating highly efficient transmission between deer.

Historically, scientists have used mice, hamsters, squirrel monkeys and cynomolgus macaques to model prion diseases in humans, sometimes monitoring the animals for signs of CWD for more than a decade. In 2019, NIAID scientists at Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana, developed a human brain organoid model for research into Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease to evaluate potential treatments and study specific prion diseases in humans.

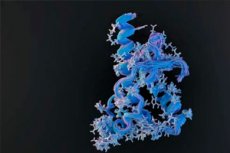

Human brain organoids are small spheres of human brain cells ranging in size from a poppy seed to a pea. Scientists are growing organoids in dishes from human skin cells. The organization, structure and electrical activity of brain organelles are similar to brain tissue. It is currently the closest available laboratory model of the human brain.

Because organoids can survive in a controlled environment for months, scientists are using them to study nervous system diseases over time. Brain organoids have been used as models to study other diseases, such as Zika virus infection, Alzheimer's disease and Down syndrome.

In a new CWD study, the bulk of which was conducted in 2022 and 2023, the research team tested the study model by successfully infecting human brain organoids with CJD prions (positive control). Then, under the same laboratory conditions, they directly exposed healthy human brain organoids to high concentrations of CWD prions from white-tailed deer, mule deer, elk, and normal brain tissue (negative control) for seven days. The researchers monitored the organoids for six months, and none of them were infected with CWD.

This indicates that even when human central nervous system tissue is directly exposed to CWD prions, there is a significant resistance or barrier to the spread of infection, according to the researchers. The authors acknowledge the limitations of their study, including the possibility that a small number of people may have a genetic predisposition that was not accounted for and that the emergence of new strains with a lower barrier to infection remains possible.

They are optimistic that data from the current study suggests that it is extremely unlikely that people will become ill with prion disease from accidentally consuming meat from CWD-infected deer.