科学家在导致儿童癌症的遗传途径方面取得了新发现,为个性化治疗开辟了新的前景。

谢菲尔德大学的研究人员创建了一种干细胞模型来研究神经母细胞瘤的起源——这是一种主要影响婴儿和幼儿的癌症。

神经母细胞瘤是脑外最常见的儿童癌症,每年影响欧盟和英国约 600 名儿童的生活。

迄今为止,由于缺乏合适的实验室方法,研究基因变化及其在神经母细胞瘤发生发展中的作用一直受到阻碍。谢菲尔德大学的研究人员与维也纳圣安娜儿童癌症研究所合作开发了一种新模型,重现了早期神经母细胞瘤癌细胞的出现,为深入了解该疾病的遗传途径提供了新的思路。

发表在《自然通讯》杂志上的一项研究揭示了引发神经母细胞瘤的复杂遗传途径。一个国际研究小组发现,17号和1号染色体上的某些突变,加上MYCN基因的过度激活,在侵袭性神经母细胞瘤的发展中起着关键作用。

儿童癌症通常在晚期才被诊断和发现,这使得研究人员无法了解导致肿瘤发生的条件,而肿瘤的发生往往发生在胎儿发育的早期。能够复制导致肿瘤形成条件的模型对于理解肿瘤的发生至关重要。

神经母细胞瘤的形成通常始于子宫内,当时一组被称为“神经嵴(NC)干细胞”的正常胚胎细胞发生突变并癌变。

在谢菲尔德大学生物科学学院干细胞专家 Ingrid Saldanha 博士和维也纳圣安娜儿童癌症研究所计算生物学家 Luis Montano 博士领导的一项跨学科研究中,这项新研究找到了一种利用人类干细胞在培养皿中培养数控干细胞的方法。

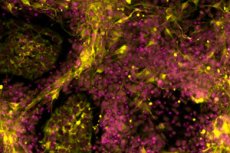

这些细胞携带着在侵袭性神经母细胞瘤中常见的基因改变。研究人员利用基因组分析和先进的成像技术发现,这些发生改变的细胞开始表现出癌细胞的行为,并且与患病儿童体内的神经母细胞瘤细胞非常相似。

这些发现为开发专门针对癌症的个性化治疗带来了新的希望,同时最大限度地减少了现有疗法给患者带来的不良影响。

谢菲尔德大学生物科学学院的阿内斯蒂斯·萨基里迪斯博士是这项研究的主要作者,她表示:“我们的干细胞模型模拟了侵袭性神经母细胞瘤形成的早期阶段,为了解这种毁灭性儿童癌症的遗传驱动因素提供了宝贵的见解。通过复制导致肿瘤发生的条件,我们将能够更好地理解这一过程背后的机制,从而制定出更完善的长期治疗策略。”

“这非常重要,因为患有侵袭性神经母细胞瘤的儿童的存活率很低,而且大多数幸存者都会遭受与严酷治疗相关的副作用,包括可能出现的听力、生育能力和肺部问题。”

圣安妮儿童癌症研究所的弗洛里安·哈尔布里特博士是这项研究的第二位主要作者,他说:“这是一次令人印象深刻的团队合作,跨越了地域和学科界限,在儿童癌症研究方面取得了新的发现。”