After traumatic events, many people demonstrate remarkable resilience, restoring their mental and behavioral well-being without outside intervention. A study led by Emory University in collaboration with the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and other institutions helps to better understand why some people recover from trauma better than others, marking a significant advance in the study of resilience.

The results of the study were published in the journal Nature Mental Health.

The study was conducted as part of the AURORA multicenter study, the largest study of trauma in a civilian population to date. The researchers recruited 1,835 trauma survivors from hospital emergency departments across the country within 72 hours of the event.

The participants had experienced a variety of traumatic events, including motor vehicle accidents, falls of more than 10 feet, physical assault, sexual abuse, or mass disasters. The goal was to better understand how brain function and neurobiology increase the risk of trauma-related mental health problems.

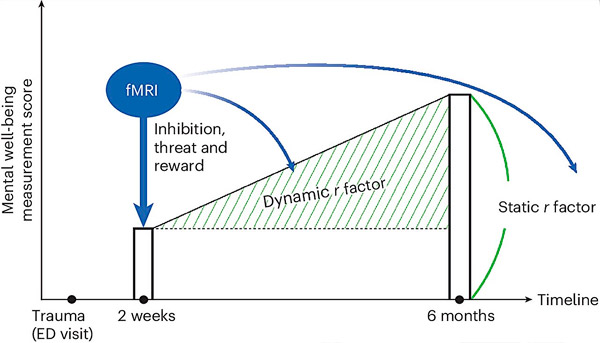

The researchers found a common factor among the study participants, which they called the general resilience factor, the "r factor." This factor explained more than 50% of the variance in the participants' mental well-being six months after the injury. The team found that certain patterns of brain function, particularly how the brain responds to rewards and threats, can predict how resilient a person will be after experiencing trauma.

"This study marks a significant shift in the understanding of resilience. Previous studies have often looked at resilience through the lens of one specific outcome, such as post-traumatic stress, without considering the multiple impacts of trauma, including possible chronic depression and behavioral changes," says study co-lead author Sanne van Rooij, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University School of Medicine.

"We examined resilience in a multidimensional way, showing how it impacts multiple aspects of mental health, including depression and impulsivity, and is linked to how our brains process rewards and threats."

By examining MRI brain scans in a subset of participants, van Rooy and her colleagues also found that certain brain regions showed increased activity in people who showed better recovery outcomes.

These findings highlight the complex interplay between neural mechanisms and resilience after trauma, offering valuable insights into the factors that contribute to effective coping and recovery processes.

Schematic overview of the study and graphical explanation of static and dynamic estimates of the r factor. Mental well-being is measured with 45 items across six clinical domains: anxiety, depression, PTSD, impulsivity, sleep, and alcohol and nicotine use. Source: Nature Mental Health (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s44220-024-00242-0

"This research shows that resilience is more than just recovery—it's how our brains respond to positive and negative stimuli, which ultimately shapes our recovery trajectory," says van Rooij.

For people who have experienced trauma, these findings may lead to more accurate predictions of who is likely to suffer from long-term mental health problems and who is not. This means that doctors and therapists could in the future use these brain patterns to identify patients who need the most support early on, perhaps preventing serious mental health problems through targeted interventions.

“We found a key factor in understanding how people cope with stress, and it involves specific parts of the brain that are responsible for attention to reward and feelings of self-reflection,” says study co-leader Jennifer Stevens, Ph.D., assistant professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine.

"Our findings have significant implications for clinical practice. By identifying the neural underpinnings of resilience, we can better target interventions to support those at risk of persistent mental health problems."