一项新研究表明,20 世纪婴儿死亡率的大幅下降使女性的预期寿命延长了整整一年。

“我想象了 1900 年美国产妇人口的样子,”艺术与科学学院克拉曼神经科学与行为项目的博士生马修·齐普尔 (Matthew Zipple) 说道,他是发表在《科学报告》杂志上的论文《降低婴儿死亡率延长产妇寿命》 。

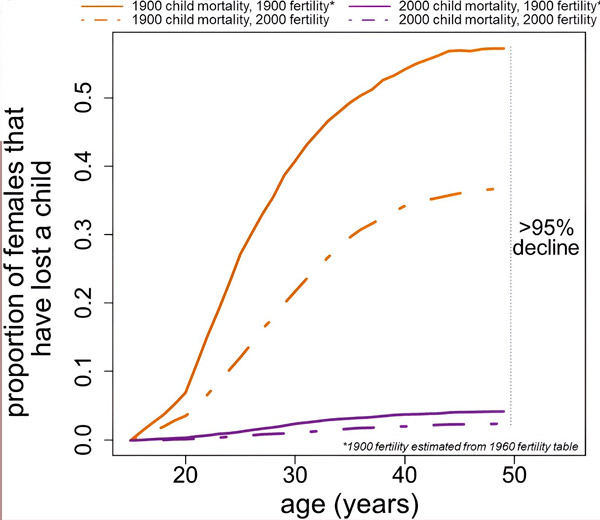

“这部分人群由两组人数大致相等的群体组成:一组是失去过孩子的母亲,另一组是没有失去过孩子的母亲,”齐普尔说。“与如今丧子之痛已经少得多的现状相比,几乎所有失去过孩子的母亲现在都不再悲伤了。”

Zipple 表示,多项研究表明,母亲在孩子去世后的几年内更容易死亡。但这种现象对父亲并不适用。

他基于美国疾病控制与预防中心(CDC)的数据,通过数学模型计算了没有悲伤对美国现代母亲预期寿命的影响。他估计,减少产妇悲伤可以平均延长女性的预期寿命一年。

作为一名研究母体健康状况与后代之间关系的博士生,Zipple 发现了非灵长类动物中,后代死亡后,母体也随之死亡的模式。在动物中,这种现象的解释是母亲健康状况不佳,无力照顾后代。

但在人类身上,同样的事件序列——后代死亡,随后母亲死亡——在以人类为中心的研究中却被解读得截然不同。相反,流行病学家和公共卫生研究人员得出的结论是,失去孩子所带来的生理和心理创伤,使母亲更容易死亡。

Zipple 在文章中引用了几项研究,这些研究将孩子的死亡与产妇死亡风险的增加联系起来。其中规模最大的一项研究涵盖了冰岛200年来不同医疗保健水平和工业化程度的母亲群体。该研究通过比较兄弟姐妹来控制遗传因素,结果表明,在孩子去世后的几年里,悲伤的父亲的死亡风险并不比没有悲伤的父亲更高。

瑞典的另一项研究表明,母亲在孩子忌日当天及前后死亡的风险高于其他时间。多项研究显示,悲痛母亲的常见死因包括心脏病发作和自杀。

“死亡风险在周年纪念日前后一周达到峰值,”齐普尔说。“除了认为这是由事件记忆引起的之外,很难得出其他结论。”

Zipple根据该研究中使用的美国疾病控制与预防中心(CDC)数据发现,1900年至2000年间,15岁以上女性的预期寿命增加了约16年。他的计算将其中一年(约6%)的增长归因于20世纪婴儿死亡率的大幅下降。

“你能想象到的最可怕的事情之一就是失去孩子。而我们已经能够将社区里这类事件的发生率降低95%以上。这太神奇了,值得庆祝。”齐普尔说道。

人们很容易忽视一个世纪以来发生的进步,因为它超越了任何一个人的一生。但过去100年里,总体预期寿命的提高,却前所未有地改善了人们的生活条件和体验。

未来的优先事项

齐普尔表示,这项研究还有助于确定改善未来的优先事项。如今许多国家的儿童死亡率与1900年的美国相似。投资降低世界各地的儿童死亡率不仅有利于儿童,也有利于整个社区。

“孩子是社区的核心,”齐普尔说。“保护儿童免于死亡,将带来层层递进的积极影响,这种影响始于母亲,但可能并不止于母亲。”