在一项新研究中,约翰·霍普金斯医学院的研究人员表示,他们已经弄清楚了狼疮症状和严重程度在不同自身免疫性疾病患者中存在差异的原因。这种疾病影响着多达150万美国人。研究小组表示,这是在理解狼疮生物学方面迈出的重要一步,并可能改变医生治疗狼疮患者的方式。

完整的报告发表在《细胞报告医学》杂志上,结论是,被称为干扰素的免疫系统蛋白的特定组合和升高的水平与某些狼疮症状有关,例如皮疹、肾脏炎症和关节痛。

干扰素通常有助于抵抗感染或疾病,但在狼疮中,干扰素过度活跃,导致广泛的炎症和损害。该研究还表明,其他常见的狼疮症状无法用干扰素水平升高来解释。

“多年来,我们一直在研究干扰素在狼疮治疗中的作用,”该研究的主要作者、风湿病学家、约翰·霍普金斯医学院助理教授费利佩·安德拉德博士说道。他解释说,这项研究的初衷是探究为什么某些狼疮疗法对某些患者无效。

“我们发现有些病例患者的病情竟然没有改善——我们想知道是否与某些干扰素组有关。”

一些狼疮治疗靶向一类特定的干扰素,即干扰素I。在这些疗法的临床试验中,研究小组观察到,尽管基因检测显示治疗前干扰素I水平较高(专家称之为高干扰素特征),但一些患者的病情并未改善。研究小组推测,另外两类干扰素——干扰素II和干扰素III——可能是导致这些治疗反应不佳的原因。

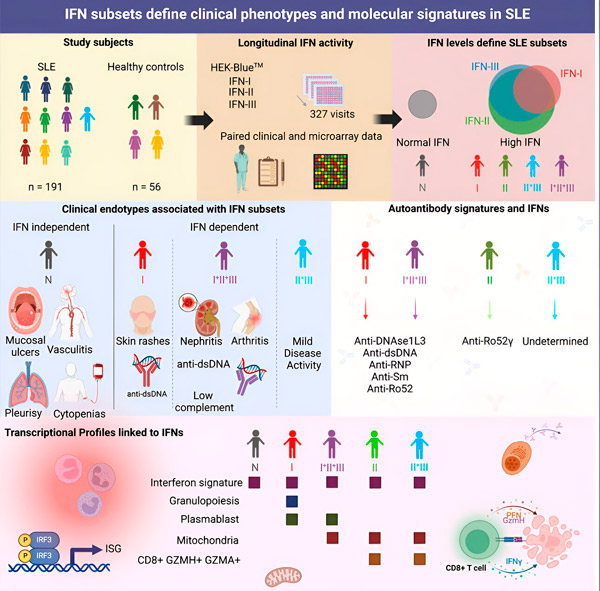

为了找到答案,研究小组观察了干扰素I、II或III的不同组合及其过度活性在狼疮患者身上的表现。研究人员从191名参与者身上采集了341个样本,以确定三组干扰素的活性,并使用专门设计的、能够对每组特定干扰素产生反应的人类细胞系对样本进行分析。

通过这一过程,研究人员确定大多数参与者属于四类:仅干扰素 I 升高的人;干扰素 I、II 和 III 同时升高的人;干扰素 II 和 III 同时升高的人;干扰素水平正常的人。

来源:Cell Reports Medicine (2024)。DOI:10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101569

研究人员利用这些数据,还建立了这些干扰素组合与狼疮症状之间的若干联系。在干扰素I升高的人群中,狼疮主要与影响皮肤的症状有关,例如皮疹或溃疡。干扰素I、II和III水平升高的参与者狼疮表现最为严重,通常会对肾脏等器官造成严重损害。

然而,并非所有狼疮症状都与干扰素水平升高有关。血栓和血小板计数低(这些症状也会影响凝血功能)与干扰素I、II或III水平升高无关。

研究人员认为,这表明这种复杂的疾病既涉及干扰素依赖性机制,也涉及其他生物学机制。研究还发现,对与这些干扰素组或干扰素特征相关的基因进行基因检测并不总是表明干扰素水平升高。他们计划在未来的研究中对此进行探讨。

“我们的研究表明,这些干扰素组合并非孤立存在;它们在狼疮中协同作用,并可能导致患者出现不同的疾病表现,”风湿病学家、约翰·霍普金斯医学院助理教授兼该研究第一作者爱德华多·戈麦斯-巴纽埃洛斯博士说道。戈麦斯-巴纽埃洛斯解释说,评估患者升高的干扰素组合可以更好地了解他们对治疗的反应,并帮助医生根据狼疮的临床亚型对其进行分组。